Your members and supporters might like to hear how the same devotion and skills that they apply in their communities are very effective abroad. They are perhaps the best way for Foreign Aid interventions to succeed.

As the title in one of my blogs states I am an “Unlikely Aid Worker”.

Saint Helena Island

My first foray abroad

was to the tiny island of St Helena, famous for Napoleon and if the Daily Mail

had its way “the world’s most useless airport”.

There I was asked to help run a local community centre. The island had about 6 such centres each

serving a district. Ours “Guinea Grass”

was the smallest and like the others barely struggled to survive with only one

or two die-hard volunteers making the effort.

My professional training was what today is called human resources, so I

set about how to motivate others to join.

None of the centres were actually membership-based even though they

served their local people. They relied on dances with the admission charges and

bar profits to go with small government grants. How do you attract more than the

regular late-night revelers who often did not turn up till the pubs closed at

11.00 pm?

Guinea Grass Community Centre St Helena Island

I learned on St Helena two things that have stood me in good stead in 40 years of community organising and activism. I call them "lifelong key take-aways".

1. Children are one of the best keys

to success. They are naturally more active and they do bring in the

adults.

2. Friendly competition between

children and adults is a major motivator and learning tool, far more effective

than teacher-centred lessons.

One event sparked mass participation and enduring interest across the island - a dancing competition with all 6 community centres. The winner by the way was Guinea Grass's Lacosta with her “Dirty-Dancing” routine.

Malawi

The Guiness Grass Centre was still flourishing when I left St Helena in 1993 for a Voluntary Service Overseas assignment in Malawi. I took over as Project Director of a UK-funded fisheries project with the aims of more sustainable catches and diversifying livelihoods away from fishing. My predecessor had formed fishing clubs, mainly for the menfolk, and “Maize Mill” clubs for the women. The idea there was that they would have their own mechanised mill to save them the hard labour of manually pounding corn for their daily meals, an idea not without occasional problems.

Rwanda

I went on from Malawi to Rwanda, to work with elderly people, and again a mixture of development activities from health to livelihoods in the immediate aftermath of the genocide and our emergency relief project to assist vulnerable people forced to return home by foot from Zaire and Tanzania. My NGO, HelpAge International, was a pioneer of working through and with local partners, as indeed was a future one Ockenden International with refugees. Again community-organising was the main methodology along with “Participatory Rapid Appraisal” for groups to decide on their own problems, priorities and solutions.

It gave us one of the most surprising findings of my career in Foreign Aid. One of the groups we formed, at the end of the exercise that lasted a week them all residing together, came up with not the usual things. Usually housing, low income, food insecurity, access to health-services led the field. No for this group, their priority was loneliness – and hey presto, we’d solved it simply by forming their community group. They’d all become good friends.

3. It led to another lifelong key take-away about the way Foreign Aid operates where surprise and unpredictability are almost anathema to the inner-circles in charge who exist in comfort zones of pre-ordained plans, outcomes and impacts - theirs - not those of "beneficiaries".

4. One more takeaway was "Be wary of the enemy within". Groups will flounder if reliant just on one or two individuals allowed to act on their own. It was the menfolk and boys on Likoma Island that betrayed their mothers, wives, sisters and daughters.

Cambodia

|

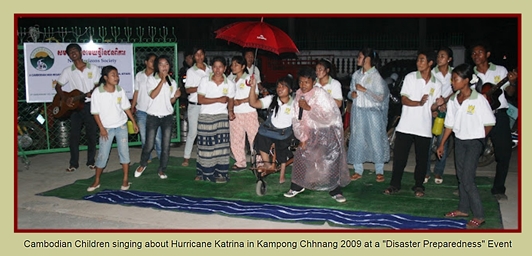

| Children, dance..... advocacy. |

In all 135 community groups were formed by this project, federating in to their own local NGO. Their most successful advocacy led to the exposure of officials purloining the modest pensions of war veterans in Cambodia.

The children’s most successful advocacy by contrast highlighted the massive failure of adults. They saw images of devastating effects of Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans. The very next year their province was flooded with no prevention measures having been adopted.

Sadly "Be wary of the enemy within" manifested its ugly head in this project as it does in others in Cambodia, along with corruption and pursuit of pure selfish and political interests.

What happened there is the subject of other blogs. Here I do not want to detract from the positive aspects from community-organising. Frequently people, adults and children, with the best leadership skills and motivation emerge over time and are not those identified during group inception. This is true in Cambodia where girls and women tend to be shy. The key to them emerging is good facilitation skills (see update below.) In fact you have to be wary of the first people to step forward where they can have other reasons for taking a lead. Usually it is to make money but often it is to promote the ruling political party. With children and young people you have to be open to late developers. One of the most surprising and pleasing cases is a member of the Child Advocacy Group who caused us most problems, took-up much time to keep him on the right path. Suddenly at the age of around 20 he blossomed, matured, went back to school, graduated, and today runs his own NGO doing exactly what he did with us. Please feel free to read about him here and to drop in to his Facebook page.

5.

Takeaway

– leave plenty room for late-developers. Take care to help identify and nurture potentially best leaders and most active members inclined to be shy and eclipsed by others.

Community organising skills have led to very successful Child Self-Protection Groups and Networks in Cambodia, in fact in my view the developed world should learn from them instead of exporting their expert-led “Safeguarding” model. Recently Police, Social-Workers and other professionals in the UK, US, Australia etc., have been found wanting yet in truth they are far more competent than their peers in Cambodia where too often they are part of the problem not the solution. Corruption is deeply-embedded as we saw when dubious orphanages proliferated as complicit authorities encouraged families to part with children for such unscrupulous people to make money from gullible tourists. In the absence of trusted officials, NGOs like LICADHO* have formed the Child-Protection Groups in the most vulnerable communities. I would argue that the same should be done in the UK based around schools and amenities that children frequent. After all it is children who usually know first when something is wrong with their friends.

My work with Ockenden International also expanded the community-organising self-help group concept that we passed on to 16 local partner NGOs, with around 870 groups, with 23,000 families as members. It is hard to select the most successful project but one candidate and the most fascinating was the Kon Kleng community that consisted of former Khmer Rouge fighters.Cow Banks are very successful community development activities. Kon Kleng’s herd numbered 80 in just 7 years. Poor families are given one cow. Its first calf is returned to the community group for another poor family.

6. Takeaway – Every foreign or external intervention should have an exit plan with a clear intention, target dates and measures to hand over to local people. In all I "localised" three international NGO operations in to locally-led ones, an all-too rare occurrence. You can read more here.

|

| Ms Mosquito with her victim |

7. Final Takeaway – Connected to being prepared to be surprised - allow your new groups to decide on their priorities, that may not be the same as yours or donors. Both poor indigenous and disabled groups wanted to proceed with "Advocacy" before they could be ready for their new livelihood activities. They said:

"We're used to being hungry. We can live with that but this new advocacy gives us a chance to do something for ourselves now!"

Salutary Warning for International NGOs and Donors.

Community-organising is often but not always initiated and facilitated by NGOs and donors. In fact the opposite is also true in Cambodia where at the turn of the new millennium and after almost two decades of expensive international assistance, people started to question its impact. Political expression then and now has always been dangerous, and therefore back in the 1990s, ordinary Cambodians on the whole being cautious left it to their international friends to articulate and advocate for them. Cambodia was dependent on Foreign Aid and therefore donors and major INGOs had some influence. Things were about to change.

|

| Click for tweet and clearer image. |

Most of that Foreign Aid was not finding its way down to poor communities. For many of them life was getting harder not better in this post-conflict development phase. Many lost land as numerous economic land concessions were given out to interests connected with the ruling party.

|

| Click for tweet and clearer image |

Nowhere was this more apparent than in communities that relied on natural resources, especially forestries that were being logged at an astonishing rate. While the official forestry monitor, Global Witness, reported the facts until it was thrown out of Cambodia in 2005, the other major conservation NGOs on the whole remained silent. Not many know this fact that I keep posting on Twitter.

Communities, some led by monks, and individuals like Chut Vutty, took to direct action and advocacy. It cost him his life. I tell his story here.

Similarly women displaced by the filling-in of a Phnom Penh lake adopted their own direct action frustrated in the same way by official intransigence and seeming impotence of the international community from major UN and international agencies to Ambassadors and NGOs. These women certainly brought their cause to hitherto unknown outside reach, and creativity, even to having the World Bank's Inspection Panel finding in their favour. ( Scroll down to Section 5)

This direct community-organising and activism has had some success, more than would otherwise have been achieved but people have paid and are still paying an expensive price for it in blood, sweat, tears, and money.

Conclusion

I hope that this article gives you more insight in to just how effective and successful community-organising can be. For more information, please visit my website and blog as per the links given.

John Lowrie

·

Declaration of Interest - I have been a Member

of LICADHO’s Board of Directors since 2005.

Update 28 June 2022

While looking through the Cambodia Film Festival brochure, to see if any indigenous people's films feature, I was pleasantly surprised to see the film on our old friend and community facilitator Sun Rotana. I recruited him and 7 others for our project in Kampong Chhnang in 2003 and he proved to be the most skilled at forming self-help groups. This was so much so that I engaged him in later projects in NW Cambodia with Ockenden and in Mondulkiri with Nomad RSI where he was particularly good with Bunong indigenous communities. He's a person of many talents and certainly a colourful character, an unsung hero. Good to see him featuring in a film.

Rotana as sent to us 2 July 2022

No comments:

Post a Comment